Since June, we have seen the NDP consistently ahead of the Conservatives in opinion polls when it comes to the popular vote. In Canada, however, what matters most is seats in parliament. As we know, it is the party that can win a vote of confidence in the House of Commons that gets to form a government, and the more seats a party has, the easier that task becomes.

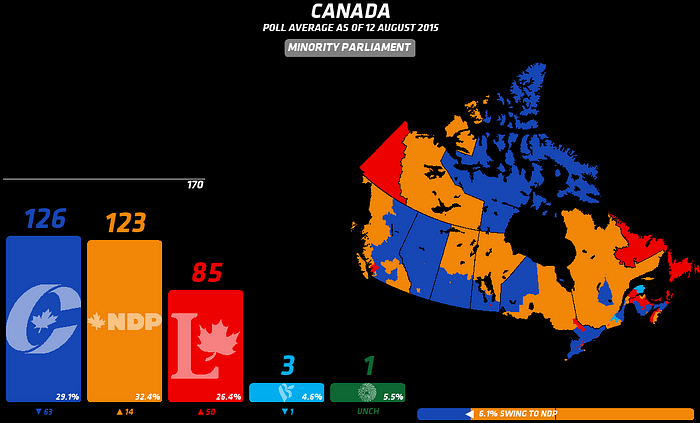

However, despite the NDP being about three percentage points ahead of the Conservatives in the popular vote in this week’s projection, it is actually the Conservatives that are five seats ahead. Constitutionally speaking, it doesn’t mean much as neither are anywhere near the magic 170 mark needed to guarantee a government, but it seems counter-intuitive that a party with the most votes could fail to win the most seats.

It would not be unprecedented, though, as this exact outcome has already occurred four times since confederation. In 1896, Laurier’s Liberals won a majority government despite finishing with fewer votes than Tupper’s Conservatives. 1926 saw Mackenzie King’s Liberals finish ahead of Mieghen’s Conservatives in seats but behind in votes. John Diefenbaker’s PCs formed a minority government in 1957 despite finishing with fewer votes than Louis St. Laurent’s Liberals. Most recently, in 1979, Joe Clark’s PCs took power away from Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals after finishing with 22 more seats, despite receiving a 5% smaller share of the popular vote.

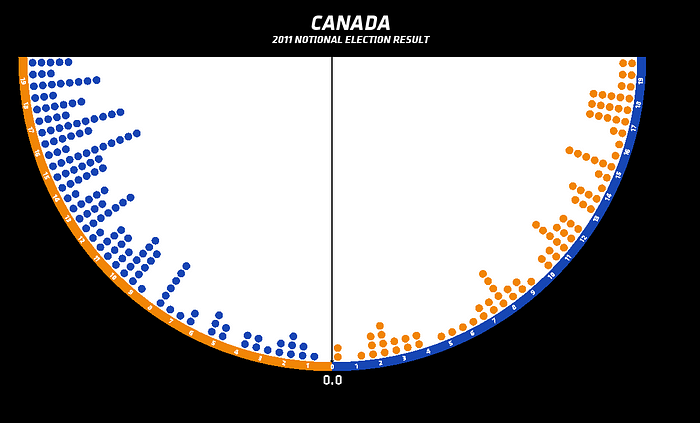

So how do we square the circle of a party with more votes getting fewer seats in 2015? For that, we borrow a visualisation popularized by the BBC since the 1960s for British elections: The Swingometer.

The swingometer is designed to measure the impact of swing on parliamentary seats. On this swingometer, we see that if 1% of voters in every riding switched from Conservative to NDP, this would only give the NDP one seat (namely Lévis-Lotbinière, just south of Québec City). A further 1% swing would give them another five. And so on.

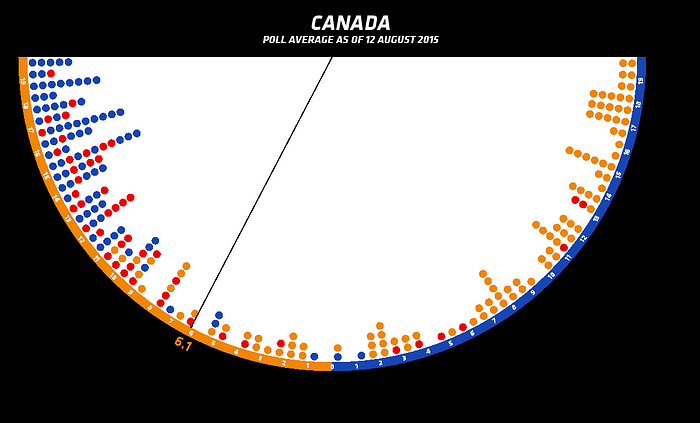

In order to draw level with the Conservatives, the NDP would need a 4.5% swing. Evidently from the polls, they are exceeding that, with a swing currently sitting just north of 6%. However, as we see by the swingometer, a 6% swing would only see 18 seats go from the Conservatives to the NDP, which would not even be enough for the Conservatives to lose their overall majority! This is because the number of seats where the Conservatives won over the NDP by a small margin is not that big, and even a 6% swing (which is not that small in a historical context) won’t really do any substantial damage.

So then why don’t we have a Conservative majority projected? Because there’s another party involved, and consequently another swingometer to consider. The first point to make is that, even if the Liberal vote stayed unchanged in each and every riding, a 6% drop in the Conservative vote would have the same effect as a 3% swing from the Conservatives to the Liberals. That swing would give the Liberals an extra 18 seats, just as many as the NDP are gaining in this scenario. This is because there are a lot more seats that the Liberals just missed in 2011 (mostly in and around Toronto), and thus a swing to the Liberals would do a lot more damage to the Tories than a swing to the NDP.

But let’s take a step back here and ask where these swings are coming from. The NDP, despite being in the lead in the polls, are up less than 2% from their 2011 result, meaning this 6% swing we’re seeing is not because of a rise of the NDP, but because of the collapse of the Conservatives (currently down 10.5%). The Liberals are up 7.5% from their 2011 result, even despite their recent drop in the polls, meaning that we’re looking at a 9% swing from the Conservatives to the Liberals. This is enough to take 36 seats away from the Conservatives (as well as a couple more in the Prairies and the Maritimes beyond this, where their swings are outperforming the rest of the country).

As for the NDP swingometer, when we show the current polling, we see that the swing to the NDP is not anywhere near uniform. In Québec, we are seeing a small swing to the Conservatives from the NDP, meaning there’s scope for a couple of Tory gains there. On the flip side, the areas where the NDP are outperforming are areas where there aren’t really a lot of seats up for grabs. The 13% swing they’re seeing in Alberta, for example, is only enough to pick up three seats there. The 11% swing they’re seeing in the Maritimes would be enough to give them seven seats, however the resurging Liberals there are reducing that gain to one. Their saving grace is British Columbia, where they’re actually able to keep most of the fruits (10 out of 12) of their 11% swing there.

Ultimately, what we need to remember is that this election isn’t one large race, but ultimately 338 separate elections across the country. If the Conservatives have enough of a buffer in enough of these ridings, that could be enough to give him the most seats, and maybe even keep him in 24 Sussex.

Note: All of these swingometers are calibrated based on the new riding boundaries, and what the 2011 result would have been had those boundaries been in force.